Anna Pauline Murray was a legal scholar, a civil rights activist beginning in the 1940s and a powerful advocate for women’s rights. She was a poet, an author and at age 60, Episcopal priest. She pioneered nonviolent civil rights protest techniques, long before Martin Luther King Jr. She developed the legal strategy to win equal rights for minorities and women. She was a superhero.

Anna Pauline Murray, born in Baltimore in 1910, became an orphan as a teen. She was 4 years old when her mother, Agnes, died. Her father, a Howard University educated high school teacher, was eventually admitted to Crownsville State Hospital for the Negro Insane in Maryland after a years long struggle with psychiatric symptoms, the repercussions of an earlier infection with typhoid. Her grandparents, Robert and Cornelia Fitzgerald brought Pauli to Durham NC to live with them and her aunts Pauline and Sallie, both teachers. Her father was killed a few years later by a white guard at Crownsville, beaten to death. Pauli had hoped to rescue her father from his hospital when she came of age, but she was only 13 at the time he was murdered.

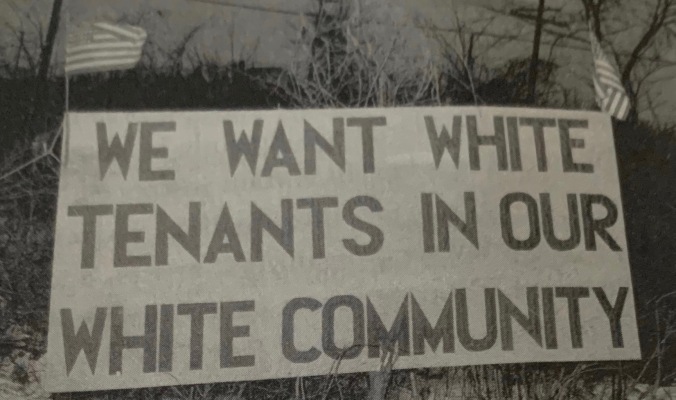

Even though she had graduated from Hillside High School in Durham, Pauli enrolled in a high school in NYC to better prepare for college. There she lived with her cousin Maude in a white neighborhood which had welcomed the family as one of their own. Her presence caused some disturbance as she was more brown skinned than Maude and could not pass for white. The tension didn’t effect Murray’s studies; she went on to graduate with honors in 1927.

One of her favorite teachers mistakenly encouraged Murray to aspire to Columbia University, an all male school. She could not afford its sister women’s college, Barnard, so she enrolled at Hunter College, a free city college. She still had to work several different jobs to pay for living expenses, books and supplies. The Wall Street Crash of 1929 interrupted her education, leaving her unable to find work like millions of others. She was able to sell subscriptions to “Opportunity”, a National Urban League academic journal allowing her to scrape together enough money to return to graduate from Hunter in 1933.

Deep into the Great Depression, Murray worked in various federally sponsored New Deal programs, like teaching in the NYC Remedial Reading Project and later the WPA, Works Progress Administration. For three months, she worked at a She-She-She Civilian Conservation camp, where she first met First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. The camp director distrusted the Black writer after finding a Marxist pamphlet among her papers. He was even more disapproving of her relationship with a white counselor, Peg Holmes. The two left camp together to ride the rails and hitchhike across the country. She kept writing freelance articles and published poems in various magazines. She also wrote a novel, Carolina Times.

In 1938, the University of North Carolina, then all white, rejected her application for admission. Ironically, one of her white forebears had been a trustee of the university. She paired with the NAACP to campaign for university admission, gaining some national attention. Murray enhanced publicity by writing to officials, ranging from the UNC president to FDR and then revealing their responses to the press in the hope of exposing their racist attitudes. But when she asked Thurgood Marshall, then leading the NAACP campaign against segregation, he refused to pursue her case. Marshall thought that living outside North Carolina for so long weakened her case at the state university. Roy Wilkins opposed the case because he disagreed with her strategy to use her letters from officials as media releases. The NAACP was concerned above all about representing respectable, “model” citizens and Pauli, a pants wearer, open about her relationships with women was anything but that. It would be 13 years later that an African American, Floyd McKissick, was admitted to UNC.

During her UNC campaign, Pauli once again interacted with Eleanor Roosevelt, this time with more extended communications. She also got involved with the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a group dedicated to ending segregation on public transportation. In 1940, while traveling with her partner on a bus in Petersburg, VA, the two women moved from broken seats in the colored section to seats in the white section and refused to move back. Pauli had made the decision to apply Gandhi’s tactics of nonviolent resistance to protest injustice. Her natural inclinations leaned more toward an in-your-face, clenched-fist-approach, but she demurred to Gandhi’s success in India, hopeful that it could be successfully employed in the US. The two were jailed. The NAACP initially defended the pair, but when they were convicted of disorderly conduct rather than a violation of Jim Crow laws, the NAACP dropped the case. The Workers’ Defense League, a socialist labor rights organization beginning to take civil rights cases, paid her fine. Murray then joined the WDL administrative committee.

During her UNC campaign, Pauli once again interacted with Eleanor Roosevelt, this time with more extended communications. She also got involved with the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a group dedicated to ending segregation on public transportation. In 1940, while traveling with her partner on a bus in Petersburg, VA, the two women moved from broken seats in the colored section to seats in the white section and refused to move back. Pauli had made the decision to apply Gandhi’s tactics of nonviolent resistance to protest injustice. Her natural inclinations leaned more toward an in-your-face, clenched-fist-approach, but she demurred to Gandhi’s success in India, hopeful that it could be successfully employed in the US. The two were jailed. The NAACP initially defended the pair, but when they were convicted of disorderly conduct rather than a violation of Jim Crow laws, the NAACP dropped the case. The Workers’ Defense League, a socialist labor rights organization beginning to take civil rights cases, paid her fine. Murray then joined the WDL administrative committee.

With the WDL, Murray worked on the defense of Odell Waller, on trial for shooting his white landlord. Waller had challenged the man for cheating him and as the man grew more menacing, he shot his landlord in self defense, fearing for his life. Pauli wrote to Eleanor Roosevelt, pleading Waller’s case. Mrs. Roosevelt wrote the Virginia governor, asking for his guarantee that the trial would be fair, a rather naive request. Black men did not get fair trials in Virginia in 1940. A Black man in Virginia did not have the right of self-defense against a white man. No all white jury, and it was all white because African Americans could not serve on juries, would set free a Black man who killed a white man. Waller was probably lucky that he hadn’t been lynched. Mrs Roosevelt later asked FDR to intervene with the governor to commute the death penalty after the predictable verdict was rendered. Not surprisingly, the governor did not and Waller was executed July 2, 1942. But the cooperation between the Black writer and the First Lady cemented a lifelong friendship between the two.

The experience with Odell Waller and her own legal case lighted the path Pauli would pick to fight for civil rights – the law. At a time when Americans were fighting WWII, opening up space in colleges for female students, Murray, the only woman, enrolled in 1941 at Howard University Law School with “the single minded intention of destroying Jim Crow.” Her strategy was an in-your-face direct challenge to Plessy v Ferguson; fight separate facilities, don’t try to make them equal.

Her tenure at Howard Law exposed her to rampant sexism at the school. On her first day, Professor William Ming casually questioned why women went to law school. Murray coined the phrase “Jane Crow” for sexism, a prejudice as firmly implanted in US law as Jim Crow itself.

The year after she started at Howard, she joined James Farmer, Bayard Rustin and George Houser, to form CORE, Congress of Racial Equality. Many CORE members were pacifists who were receptive to Pauli’s nonviolent resistance strategy to win civil rights. She also planned sit-ins in local Washington DC drugstores and cafeterias. Her signs read “We Die Together, Why Can’t We Eat Together?

Pauli continued to write. She published an article “Negro Youth’s Dilemma”, challenging segregation in the US military during WWII. She wrote her most famous poem on race, Dark Testament, during this period, although it was not published until 1970. She published two important essays in 1943, “Negroes Are Fed Up” in Common Sense as well as an account of the Harlem “race riot” in New York Call, a Socialist newspaper. All of her activities predated the rise of the broader civil rights movement and MLK’s strategy of nonviolent resistance by almost 2 decades. Her vision evolved before her Black brethren were ready to see it.

None of Murray’s activities kept her from achieving academic excellence. She was elected to the highest Howard student position, chief justice of the Court of Peers and graduated first in her class in 1941, no easy feat given the subjective grading of male professors prejudiced against women. That position should have won for her the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship at Harvard, then a male only college. She was once again rejected by a university; this time, she had two strikes, one for gender and one for race. She appealed to the school to make an exception in a snappy letter, “I would gladly change my sex [if that were possible], I have no recourse but to appeal to you to change your minds. Are you to tell me that one is as difficult as the other?”. The University won’t budge even with a letter from FDR.

Instead, Murray chose the University of California Boalt School of Law where her Masters thesis, The Right to Equal Opportunity in Employment, was published in the California Law Review. After passing the California bar, she went on to become the state’s first Black deputy attorney general in 1946. She was named the National Council of Negro Women “Woman of the Year” (1946) and Mademoiselle picked her for the same title the following year.

States’ Laws and Race and Color, a book which critiqued state segregation laws was published in 1951. Using an innovative technique, she drew on the law, psychology and sociology to argue that civil rights lawyers should challenge segregation laws as unconstitutional head on, rather than argue “separate but equal” was unequal as practiced. Thurgood Marshall, then chief counsel for the NAACP took up her approach for arguments in Brown v Board of Education (1954), including the use of studies in sociology and psychology in the briefs. Together with later cases, he successfully overturned segregation laws, although it was years before integration in schools and facilities that serve the public actually occurred.

Soon, she was swallowed up by the Joseph McCarthy committee, resulting in the loss of an offer for a position at Cornell University. She had, after all, published in socialist newspapers, worked with socialist workers’ organizations. There were rumors about communists in civil rights organizations. McCarthy painted everyone on the left with a broad red brush of communism, using innuendo, fear and intimation, with the intention to ruin the lives of liberals. He was a demagogue who used his Senate platform for fame and political advancement. Cornell University officials explained that the liberal credentials of her references, Eleanor Roosevelt, A. Philip Randolph and Thurgood Marshall had not helped her case and their duty was to protect the institution from the vagaries of the turbulent time.

By 1956, Pauli had written and published a biography of her grandparents and their struggle against racism in Durham NC, Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family. This exploration of her family’s story stimulated thoughts about the complexity of her family’s roots. Although her family history was a veritable melting pot of white, Black and Native American members, she felt the tug of Mother Africa and so, travelled to Ghana in 1960. There she taught at the Ghana School of Law for 2 years.

On her return, she served on the Commission on the Status of Women appointed by JFK and chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt. There she drafted a memo that argued that the 14th amendment applied to gender based as well as racial discrimination.

Pauli had become disenchanted while working in the civil rights movement with A Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin and Martin Luther King. She bristled against movement domination by men and their treatment of women. Women handled the bulk of the day to day arrangements and much of the grassroots organizing and yet they were excluded from national policy making decisions. They cooked, cleaned, provided transportation, raised bail. They typed letters, printed leaflets, staffed offices. Men were the nationally known faces and spokesmen of the civil-rights movement. Underlying the tension was a narrative that cast Black women as domineering and emasculating. Black Power advocates and the Black Panthers were the most vocal about women submitting to male leadership to support Black manhood, long denied by whites. One Black Panther said bluntly that a Black woman’s place in the movement was flat on her back.

Many working in CORE, NAACP, and SCLC projects came from Black churches where male leadership was the accepted norm. Most women assumed that their role would be ancillary but in doing so, they felt that they were making an important contribution. By 1963, she was ready to go public, giving a speech to the National Council of Negro Women. Murray also expressed her view in a letter to Randolph, citing the “blatant disparity between the major role which Negro women . . are playing in the crucial grassroots levels . . .and the minor role of leadership they have been assigned in the national policy-making decisions. It is indefensible to call a national march on Washington and send out a call which contains the name of not a single woman leader.” The occasion was the planning of the 1963 March on Washington. No women were invited to speak or included in the delegation to go to the White House.

- Photo by Rosemary Ketchum on Pexels.com

By 1965, Murray became more active in the movement for women’s rights. She co-founded NOW, National Organization of Women in 1966, an organization she envisioned would become a women’s NAACP. She published the George Washington Law Review landmark article “Jane Crow and the Law: Sex Discrimination and Title VII” which tied the application of Title VII in the recent Civil Rights Act to discriminatory laws against women, likening them to Jim Crow laws, an idea she had germinated during her early days at Howard when she first coined the phrase. Along with Dorothy Kenyon, she argued and won White V Crook in the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit which held that women have an equal right to serve on juries. Ruth Bader Ginsburg acknowledged Murray’s legal advances in the fight for women’s rights when she named Murray and Kenyon coauthors in her Reed v Reed brief, the 1971 Supreme Court case that extended the 14th amendment equal protection clause to women. As part of her brief, Ginsberg cited Pauli’s legal underpinnings for using the 14th amendment to defeat discrimination by gender.

The Black attorney held several academic positions. She served as vice president of Benedict College for a year and then moved to Brandeis University as a professor. Over 5 years, she introduced courses in African American studies and women’s studies.

Pauli, increasingly involved with the Episcopal Church, left Brandeis at age 60 to become a seminary student, ultimately joining the first group of female Episcopal priests to become the first Black woman to be ordained. She settled in a Washington, D.C parish, working with the sick.

Pauli Murray died of pancreatic cancer in Pittsburgh in 1985. She was a giant in the civil rights and women’s rights movements. As early as the 1940s, she anticipated the nonviolent resistance of the civil rights movement, organizing sit-ins in Washington D.C. As a poet, writer, and lawyer, she fought for equal rights, an early advocate for fighting segregation directly as a violation of the 14th amendment that became the signature of the NAACP’s challenges to segregation. She co-founded CORE. She called out sexism in the civil rights movement and when the time was right, co-founded NOW. Her concept of Jane Crow was central to her legal attack on discrimination against women, later carried forward by RBG. In addition, her efforts were critical in retaining the word “sex” in Title VII, which provides legal protection for women against discrimination in employment.

In 2017, her family home in Durham was named an Historic Landmark in the National Park Service.

MARCH 10, 1865

Confederate forces in South Carolina hang an enslaved Black woman, Amy Spain, for aiding the union army.

March 11, 1965

Reverend James Reeb, a voting rights supporter dies 2 days after he is beaten by an angry white mob in Selma Alabama